In August, as President Barack Obama stood in front of the Disabled American Veterans Convention and publicly hailed the success of a new health care enrollment app on Vets.gov, the system had actually been spinning out of control for months, losing thousands of applications, locking records, and allowing officials to mark veterans ineligible for benefits without legal justification, according to hundreds of pages of internal documents obtained by MeriTalk.

Senior VA officials had told the White House that the system was helping to solve the enrollment challenges faced by VA. But unknown to the president, employees throughout the Health Eligibility Center (HEC) within the Veterans Health Administration had been virtually blindsided by the June 30 public launch of the Online Health Care Application through Vets.gov. Emails dating back to April show that VA employees responsible for enrolling veterans around the country had no idea how the new application process worked, and began notifying senior officials of major problems with lost applications and locked records.

“When we got notification of Vets.gov, we got it from a June 30 email from Bob Synder, the interim chief of staff,” said the VA whistleblower who provided the documents. “Nobody knew that they had actually turned on the health care application on Vets.gov. We worked at HEC and we found out when the nation found out.”

According to the whistleblower, it was well known during the rollout of the software that significant glitches existed. Documents and emails reviewed by MeriTalk confirm the existence of complaints from VA employees across the more than 150 VA hospitals and community–based outpatient centers.

Prior to the activation of the health enrollment application on Vets.gov, VA enrollment specialists across the country began flooding the email inboxes of the HEC with complaints of missing data, incomplete information, and data inconsistencies that automatically created locked records.

“We have had ZERO online registrations since last Thursday. This is VERY unusual for us,” an enrollment coordinator in North Carolina wrote July 20. “We’ve had veterans fax us their DD-214 [service record] and call asking if they were eligible for care, and they are not in our system. So that tells me that the application (as I originally feared) is not going to [the HEC in] Atlanta. But where are they going? I am in panic mode thinking there is a possibility that veterans may well could have applied online and the information is not submitting to us as it should be.”

That’s exactly what was happening, according to the documents. As many as 9,000 online applications failed to be submitted properly. HEC staff has been working overtime for months trying to process those applications, but many may have been lost for good. As late as Aug. 25, the acting director of HEC’s Enrollment and Eligibility Division had formed an “HCA Locked Records” project. An email with the subject line “Overtime Extended to others” called for volunteers to help process more than 8,400 locked records.

“The whole time they knew they were losing applications through failed submissions,” the whistleblower told MeriTalk. “Nobody knew where some of these applications were. They’re still trying to find out.”

In addition to losing applications, many enrollment professionals throughout VA simply didn’t know how the new software worked and how to enroll veterans. Less than a month before Obama was scheduled to appear at the DAV Convention, HEC employees were scrambling for help understanding how the new enrollment process worked through Vets.gov.

Enterprise Confusion

VHA enrollment coordinators didn’t know how the information on the veteran applications was transmitted from Vets.gov to the Enrollment System (ES), a workflow management system developed in 2009 and used by HEC employees. In addition, hospital staff conducting enrollments used the VA main electronic health record system, the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA), to process enrollments.

“Enrollment and eligibility in VA is decentralized. Every hospital is responsible for processing applications that they receive. The HEC processes a small percentage of applications that are received there. But the HEC has very little visibility into enrollments in the field,” the whistleblower told MeriTalk. “VA does not have an enterprise system to function as a repository for applications. And there’s no mandate for VA employees to use one system to enroll veterans.”

When hospitals use VistA to enroll a veteran, the record doesn’t transfer instantly to the Enrollment System at HEC. “There’s at least a 24-hour lag time. And even then, we don’t know if the hospital employees entered all of the information from the veteran’s application or if it’s correct. Because if you’re at HEC, you can’t see the original application,” according to the whistleblower.

Enrollment professionals in Texas and Florida reported just 10 days before Obama’s appearance at the DAV convention that data inconsistencies and blank fields, such as missing information on the veterans means test (the financial determination if the veteran qualifies for health services), were automatically causing system errors and locked records.

“We get these alerts from HEC [that state] ‘The Health Eligibility Center has added a person to your database.’ If this is the case then why is so much missing?” wrote a senior patient processing and benefits administrator in Florida in an email addressed to all VHA enrollment coordinators. “All of these have our parent facility listed, and knowing by the address that the veteran could pass by at least two other facilities they probably do not want the parent facility. But having no way to contact the veteran we don’t know where they want to be seen.”

Fraudulent Applications

The frustrations of HEC and hospital staff have their roots in a 2015 inspector general report that skewered the VHA for creating a backlog of more than 889,000 health care applications that had been placed in a pending status, sometimes years after submission.

The man at the center of the controversy is Matthew Eitutis, a former director of the Health Resource Center, who was appointed to oversee VHA’s response to the IG report and its recommendations. In January, Eitutis was named acting director of Member Services, an umbrella organization overseeing the Health Resource Center and the Health Eligibility Center.

But documents submitted recently to VA Secretary Robert McDonald and Deputy Secretary Sloan Gibson accuse Eitutis of fostering a hostile work environment by taking punitive actions against personnel who voiced concerns about problems with the system. Guidance documents obtained by MeriTalk also show that Eitutis instituted a program called the Veteran Enrollment Re-Work Plan (VERP) and directed employees to notify veterans that they are “ineligible” for VA care “due to lack of military service information” in their applications.

“I have reviewed a sample size of the records and the ineligible reason for some states ‘No application on file.’ That is not an established reason to warrant a veteran ineligible,” an HEC official wrote in an email dated May 10.

“Due to VERP instructions, all of our sites are having increased ineligible veterans showing up, ” wrote a VA program analyst in Nevada.

Veterans can only be tagged ineligible if he or she had served less than 24 months or received a dishonorable discharge that had been verified by the Veterans Benefits Administration. Few, if any, of the applications in question met these standards.

“But just because you can’t locate a veteran’s DD-214 is not a legal reason to find an applicant ineligible for veterans health services,” the whistleblower said. “Because veterans that served in the pre-Vietnam era did so when there was no automation. We typically get that information from a family member. It may not be in DoD’s database and VHA may not have access to it electronically. They did reduce the number of pending applications. But the way that they went about it was fraudulent.”

This is not the first controversy surrounding Eitutis. Another whistleblower, Scott Davis, revealed that the veteran hotlines operated under Eitutis at the Health Resource Center had a call “abandonment rate” of 26 percent during 2015. The average wait time for an answer to a call into the Health Resource Center phone banks was two to six minutes during 2015, according to the data.

In February, Gibson moved responsibility for the veteran suicide hotlines from medical officials to the HRC run by Eitutis. One veteran is known to have committed suicide because he could not get through to the hotline.

Moving Backward

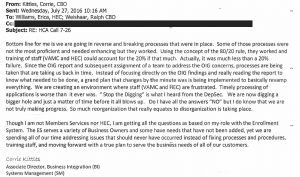

Just four days before Obama was scheduled to take the stage at the DAV Convention and tout the successes of the online application process through Vets.gov, Corrie Kittles, the associate director of Business Integration within the VHA’s Chief Business Office, notified Erica Williams, the deputy director of the Health Eligibility Center, and Ralph Weishaar, the assistant director of compliance at the Health Resource Center, that the new application process was severely broken.

“Bottom line for me is we are going in reverse and breaking processes that were in place,” wrote Kittles. “Since the OIG report and subsequent assignment of a team to address the OIG concerns, processes are being taken that are taking us back in time. A grand plan that changes by the minute was being implemented to basically revamp everything. Timely processing of applications is worse than it ever was,” she said. “We are now digging a bigger hole and just a matter of time before it all blows up.”

In an interview with MeriTalk, the whistleblower acknowledged that the VERP effort and the direction of senior officials “probably set enrollment back a year.”

On Aug. 1, Obama took the stage at the DAV Convention at the Hyatt Regency in Atlanta.

“We need to keep making it easier to access care,” Obama said. “That’s why we recruited some of the best talent from Silicon Valley and the private sector. And one of their very first innovations, veterans can now finally apply for VA health care any time, anywhere, from any device, including your smartphone—simple, easy, in as little as 20 minutes. Just go to Vets.gov. The days of having to wait in line at a VA office or mailing it in—those days are over.”