But I digress. This is why we need to have a strong, empowered CIO at agencies. When Evans was the CIO at Energy, she often jokes that you couldn’t throw a rock without hitting 10 of them. But by the time she left and went to OMB, she had quashed them all. The reason this is important is because if everyone is in charge, no one is in charge. In the chapter on Enterprise Architecture, I talked about specifying the strategy in the IRM Strategic Plan. But what happens when each bureau CIO develops his or her IRM strategic plan? Chaos. Fragmentation. You definitely won’t get enterprisewide capabilities. You really do need one ring to rule them all. You need someone with the authority to prescribe how it should work, especially when people disagree.

The Department of Energy is such a classic case on this problem because the central office really has no authority or power. I would submit that the Secretary doesn’t even have the power to bring the labs into alignment. Evidence of this is the fact that they have buried the CIO under layers of bureaucracy to render him impotent. The current CIO can’t even compel good behavior for something so obvious as including a supercomputer, a billion-dollar investment, as an IT capital asset.

Let alone the fact that you might want to go after the duplicative, redundant, and wasteful investments like multiple email systems, multiple document management systems, multiple data centers. The Department of Energy reports only 30 total data centers. Heck, the CIO there isn’t even allowed to count how many data centers they have, so forget about trying to put together a plan to close some of them.

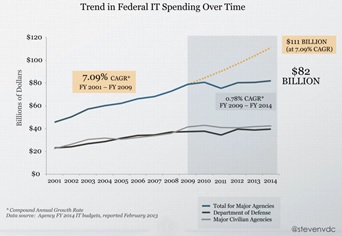

While the Department of Energy is an egregious case, it is not the only one. Following the passage of the Clinger-Cohen Act and through the 2000s, CIOs existed and were generally relegated to running the desktop helpdesk and back-office capabilities of agencies. They weren’t consulted on most IT acquisitions. Spending on IT rose dramatically from the $26 billion in 1996 to the nearly $90 billion today. This slide from former Federal CIO Steve VanRoekel demonstrates that growth in spending through about 2010 when the slowdown in the economy affected agency budgets. As you can see, 2010 marks a change in the IT budget. Expenses didn’t decrease, but budgets sure did. As a result, we needed to figure out how to keep delivering the same level of service with less money. That is why M-11-293 was so important.

That memo, signed in August of 2011, breaks from the previous principles from the 25-Point Plan and focuses IT on driving operational efficiency. As everyone knows, when money gets tight, look in the cushions of the couch. Well, that is what M-11-29 was trying to do, and it became the roadmap for how to fix Federal IT.

When we start looking for opportunities to drive efficiency, the first is to implement those fundamental changes that I talked about in the Commodity IT chapter. Look at the fragmentation of the buying for a specific commodity and focus on making that as efficient as possible. To do that we need agencies to aggregate their acquisitions. The amount of resistance to that was really high. Most CIOs complained like Simon Szykman, the former CIO at Commerce:

“I control less than 2 percent of the department’s IT spending, and the rest of it is managed out at the bureaus. Most of them have their own CIOs who have their own IT budgets and staff, so just the ability to get things done in an environment where you don’t have direct management line of authority and control over all the decision-making is a challenge.”4