The Situation Report: Comey’s Encryption Comeback

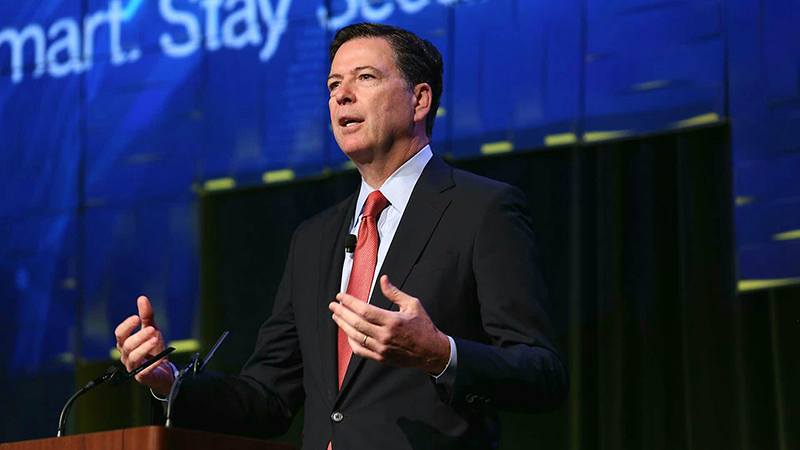

FBI Director James Comey speaks Aug. 30 at the Symantec Government Symposium in Washington, D.C. (Photo: MeriTalk)

Your humble correspondent got a chance to ask FBI Director James Comey about his views on the recent hacking attempts against election systems in Arizona and Illinois. But his answer to my question at the 13th Annual Symantec Government Symposium paled in comparison to his renewed counterattack against Silicon Valley’s stance on ubiquitous encryption.

Comey expressed serious concerns about large swaths of the Internet “going dark,” becoming effectively out of reach of legitimate law enforcement and national security investigations. We should all be concerned about that. But Comey may have reignited the war of words with Silicon Valley when he basically told the tech industry’s giants that it’s not their place to decide national policy that would fundamentally alter the privacy bargain that has been at the heart of democracy in America since its founding.

“The FBI’s role is not to tell the American people how to live and how to govern themselves,” Comey said. “And it’s also not the job of tech companies, as wonderful as they are, as great as their stuff is, to tell the American people how to live, how to govern themselves. Their job is to innovate and sell us great equipment. The American people should decide: How do we want to live? How do we want to be governed? How do we want to govern ourselves?”

That was an astonishing rebuke of Apple CEO Tim Cook and other Silicon Valley high priests who signed an open letter in April to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence calling for an end to government mandates that would grant access to encryption keys for law enforcement and national security purposes.

Comey accused the tech industry of attempting to force a policy upon the nation that would fundamentally alter the “reasonable expectation of privacy” bargain struck between the government and the governed.

“Even our memories are not absolutely private in the Unites States,” Comey said. “Even our communications with our spouses, with our lawyers, with our clergy, with our medical professionals are not absolutely private. Because a judge, under certain circumstances, can order all of us to testify about what we saw, remembered, or heard. There are really important constraints on that. But the general principle is one that we’ve always accepted in the United States and has been at the core of our country: There is no such thing as absolute privacy in America. There is no place outside of judicial authority.”

And when it comes to the issue of encryption? “Widespread default encryption changes that bargain. In my view it actually changes the bargain at the center of our country,” said Comey.

For Comey, that bargain is based on Americans’ reasonable expectation of privacy “in our houses, in our cars, in our safe deposit boxes, in our devices.” The government cannot invade our private spaces without good reason, good reason that is subject to court approval, he said. “But it also means that with good reason the people of the United States, through judges and law enforcement, can invade our public spaces. That is the bargain that has been at the heart of the liberty of this country since its founding.”

Shortly after Comey’s presentation, I asked Nuala O’Connor, the president and CEO of the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) and the first Federal chief privacy officer at the Department of Homeland Security, what she thought of Comey doubling down on his encryption stance.

O’Connor, who knows and admires Comey, offered a simple counterargument: “He could not be more wrong on encryption.”